10 Best Sedans for Snow Autobytel.comautobytel Car-buying-guides Features

Greg Ross didn't see it coming.

He should have. A graduate of Kansas State University with a degree in journalism, he wrote ads and brochures for car dealerships for a spell, earned a car broker's license in 1995, then started a company in California called Market Place Motors. Today, Ross, who is 40, locates luxury cars for buyers too busy to do it themselves—for execs at Warner Bros., for instance.

In the fall of 2000, Ross heard an odd story. It went like this: A man named John Bowers had died, leaving an estate valued at $411 million. The estate was still in probate, with 13 lawyers beavering away at litigious details, among them the liquidation of the company cars that Bowers had amassed during his career at a Texas-based company called Mission Foods. There were thousands of cars in the estate, all '98 and '99 models, most with fewer than 10,000 miles. The majority were workaday sedans—Camrys, Accords, Tauruses—but there were also a number of "executive cars"—Navigators, S-class Benzes, Sevilles, even a few Bentleys. The sheer number of cars was allegedly creating a tangle of red tape, so the lawyers had opted to sell them for whatever each represented as a tax liability to the estate's sole heir. That heir, incidentally, was a troubled L.A.-area youth whom Bowers had adopted in an act of Christian kindness.

Greg Ross was intrigued but cautious. "One of those too-good-to-be-true things," he remembers. "But I thought it wouldn't hurt to ask for a list of cars from a guy who knew all about them." That list turned out to be short on details—no exterior colors, no options, no transmission types, no VINs. The list simply said: "Offered: 1998 Honda Accord, $1000 apiece (10 available); 1998 Toyota Camry, $1000 apiece (10 available); 1998 Mercedes-Benz SL500, $5000 apiece (20 available)."

"I wouldn't have touched it," says Ross today of the 40 cars on that list, "but I had a car-dealer friend who'd already invested—a guy with 20 years of experience. So on October 30, 2000, I did it, purchased everything on the list, had my bank wire the whole $120,000. I got back a generic receipt, the kind you buy at a dimestore. I was told to be patient, to wait for the cars to be released from probate. I asked again for VINs, but they told me details were impossible because of a gag order—a Judge Jack Lomeli was already mad at outsiders poking into the estate's affairs. But I work with banks a lot, so it wasn't hard for me to track where my money went. It wound up in a California account belonging to James R. Nichols. I thought, Well, that makes sense. I'd heard his name mentioned as the executor. And, anyway, whenever I got cold feet, I'd call and they'd say: 'Listen, guys are lined up to buy these cars. You want a refund, just say so. You'll get your $120,000 back in a cashier's check in 10 days, no questions asked.' After that, I'd have this daily discussion with myself. I'd say, 'Well, I'll just keep monitoring this. I'm not a kid, not emotionally attached to these cars. I can bail any time.' I'd con myself into waiting a little longer."

"Con," it turned out, was an interesting choice of words.

Native Californians James R. Nichols and Robert Gomez first met in September 1994. Both were 19. Both had graduated from high school and taken a series of minimum-wage jobs around Los Angeles. Now they were working together as security guards. It was boring work, but there was plenty of time to talk. Nichols told his new friend that he wanted to join the LAPD. Gomez said he wanted to be a professional poker player. He added that he was adopted, and his father—a corporate big shot who wasn't around much—was extremely well off.

A month later, sure enough, a man identifying himself as Gomez's adoptive father came to town. The boys drove to meet him at a country club in Long Beach. "He was waiting in the pro shop," remembers James Nichols. "Big Caucasian guy, maybe 250 pounds, polo shirt, khaki pants, sunburned, with hair plugs. He told me to keep an eye on Robert, keep him away from drugs and alcohol. I said I'd try, that Robert was my friend. We talked for 10 minutes. Then he said: 'You know who I am, don't you? My name is John Bowers.'"

Young Gomez and Nichols resented spending their meager incomes on rent. In December 1994, they moved into the home of Nichols's parents in the blue-collar suburb of Carson. They shared James's old bedroom, in fact—car posters still on the wall. James's parents, Sam and Rose, warned the boys there'd be no hanky-panky as long as they lived under the family roof: no drinking, no girls, no swearing. Rose insisted the boys accompany her weekly to Christ Christian Home Missionary Baptist Church, in nearby Compton. Both agreed.

James Nichols is an African-American with caramel-colored skin. He is as handsome as Adonis and as athletically blessed—thin hips and waist, powerful chest, square shoulders, a voice as deep and mellifluous as Barry White's. He is aggressively polite, referring to adults as "sir" or "ma'am." He is serious and solemn. It is difficult not to like him.

Robert Gomez is Hispanic, with a round face and protruding belly, tinted glasses, a dainty mustache, a shaved head. His friends call him "Buddha," and it's easy to see why. He is quick to smile and finds something upbeat to say at every opportunity. He travels nowhere without a book of crossword puzzles, which he works with the concentration of a Zen master. He is amusing, affable, occasionally clownish.

Despite their rudimentary educations, both Nichols and Gomez speak like worldly adults—clearly, confidently, without errors of grammar. Nichols speaks deliberately, pausing to select words. Gomez speaks in a torrent, often omitting the final words of a sentence to rush to a new thought.

Nichols and Gomez coexisted serenely in the Carson house for a year, and not much happened. Then, in the fall of '95, James and his parents began receiving phone calls from three men claiming to be attorneys for John Bowers. Bowers, they said, had died suddenly on October 23.

Two more years passed. Gomez sometimes mentioned his dad's estate—it was huge, he said, worth $411 million—but details were few. Then one Sunday in early '98, Gomez did a curious thing. He stood up in church to address the congregation.

"He told our members he was a recovering alcoholic," remembers Rose Nichols, "and he wished the church to pray for him. He promised our reverend $100,000 once his father's estate was settled. He said there were 16 vehicles of his father's, too, and he'd sell them for the amount of tax and licensing—$1000 or $1100. He called them 'errand cars,' 'runabouts.'"

Gomez let it be known that the cars, per John Bowers's instructions, were to go to Christians who acted in accordance with the Bible's teachings. Such persons, Bowers had reportedly said, deserved a miracle in their otherwise difficult and dreary lives. "Someone called them 'Miracle Cars,'" recalls Rose Nichols. "That name stuck."

Gomez's brief speech produced immediate results. Church members flocked to Rose—whom they knew better than Gomez—with checkbooks in hand. Gomez firmly reminded that personal checks would not do. The lawyers would accept money orders or cashier's checks only.

It didn't slow anybody down.

Almost overnight, Rose Nichols sold $30,000 worth of cars—was selling, more accurately, the promise of cars. "They went to my brothers and sisters, three members of the church, nine other relatives," she says. She handed the proceeds to her son and to Gomez, who reminded her that no cars could be delivered until the estate cleared probate. Soon after the first batch of Miracle Cars was snapped up, Gomez revealed he could get more, that the estate was overflowing with vehicles, and not all of them were cheap "errand cars," either. Rose continued selling—wasn't so much selling as simply answering the phone and taking orders. Before long, she'd sold $1 million worth. It was wearing her out.

The proceeds were supposed to be funneled to a non-interest-bearing escrow account at Chase Manhattan Bank. Instead, the funds flowed mostly to Robert Gomez. No one was alarmed—he was the heir and would get the money sooner or later. It turned out, however, that Gomez was using the funds to pursue his dream of becoming a pro gambler. He'd already become a fixture at the Bicycle Casino in nearby Bell Gardens, one of five such Southern California card parlors.

In September 1998, Gomez showed his will to James Nichols. It was sloppily and hastily handwritten on a store-bought "E-Z Legal Form." In part, the will read: "I, Robert Gomez, declare James Randall Nichols as the executor of my estate."

"I looked it over and agreed to serve," remembers Nichols, who then, oddly enough, represented himself as the executor of Bowers's estate. "I was to handle all the refunds and keep the records straight. I was told I'd get a 12-percent fee and a $5000-per-month salary. It was more like eight hours a day, so I quit my day job."

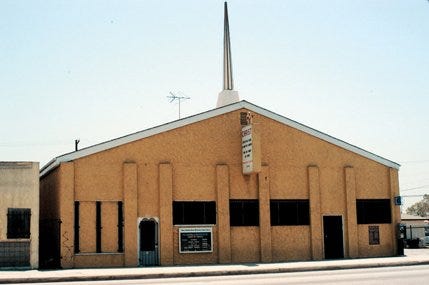

Rose Nichols wanted to quit her day job, too. She was sick of selling autos out of her modest little house. It was thus a minor miracle when a Memphis woman named Gwen Baker called late in 1998. Halfway across the country, the 48-year-old Baker, a correspondence school "doctor of divinity," had heard about the Miracle Cars. She hoped to purchase one herself—wanted a Jaguar but settled for a Cadillac STS. More important, Gwen Baker made it known she was a towering figure among Midwest Baptists. If these Miracle Cars were intended as blessings for the devout, then it was surely she who could corral a pool of potential purchasers.

Nichols and Gomez liked the idea. They hired Baker as a "finder"—essentially as a sales manager who could also set up a central office for operations. "So they gave me lists of cars," Baker recalls, "and said I'd get 17 to 18 percent [commission] on what I sold. Mr. Gomez said he had the approval of the [estate's] board of directors to do this. Later I was paid $30,000 per month in salary. I was told to take it out of what cars I sold."

Baker attacked the job like a woman possessed. She was organized and kept impeccable records. So much money began flowing into her Memphis office that Nichols flew there seven or eight times just to pick it up. On one trip, he had his picture taken as Baker handed him an envelope stuffed with $200,000 in cash. Baker began calling Nichols and Gomez her "godsons."

Baker was most effective when she worked through the pastors of churches, letting them tell their parishioners about the cars for sale. Sometimes, though, she spoke at church functions herself. At one such gathering, Baker said: "We're working diligently on the probate, but it's such a large estate it's not an easy task. I guarantee you God has an agenda to open His hand and release these assets, but remember, you can lose the Promised Land by grumbling and complaining. It's not easy to turn over your hard-earned money to me. But once God has put His stamp of approval on this—as He has—forget about it and wait. Thanks for purchasing cars. God wants you to prosper. God wants you to roll."

WIn the late summer of 1999, the pastor of a Memphis church, who had put up some money for a Rolls-Royce from the estate, put Baker in touch with a pastor in tiny Higginsville, Missouri, just outside Kansas City. The Missouri pastor's name was Corinne Conway, the 59-year-old founder of what she called the Virtuous Women International Ministries. Conway quickly evolved into a "finder" every bit as motivated as Baker. With Conway on board, Nichols and Gomez now had in place the final piece of a national network—a Miracle Cars dream team.

Conway was a natural-born salesperson, pitching to rich and poor alike, not just to retiring churchgoers. She sold $12,000 worth of cars to an elderly and impoverished seamstress. She sold $700,000 worth of cars to former NFL players Neil Smith and Ricky Siglar. She even sold cars to the cynical general manager of a Lincoln Mercury dealership. To pay for her expenses, Conway began charging a finder's fee. At first it was $50 per car, though it later grew to $1000.

The money didn't just flow in. It gushed in torrents. Conway quickly logged $6 million in sales, which she handed to Baker, who forwarded it to Nichols and Gomez in L.A. In the year 2000, Conway drummed up $992,000—not in car sales but in finder's fees alone. She kept it for herself.

The well seemed bottomless. In just two months in 2001, Baker and Conway—the Maris and Mantle of Miracle Car sales—sold $1.46 million worth of cars across the Midwest. It didn't take long before they'd racked up 7000 sales to 4000 buyers from New York City to Newport Beach.

The influx of cash nearly swamped Nichols and Gomez back in California. Nichols finally had to establish a business account—and did so in September 1999 at the First Bank & Trust in Lakewood. He couldn't keep flying across the country to pick up sacks of cash and checks, and he needed ready access to cashier's checks for buyers demanding refunds. More taxing was this: The two men now faced the not inconsiderable chore of discreetly disposing of many millions of dollars. Nichols had his own method: In just 22 months, he purchased a $44,195 Ford Excursion, a $29,045 Mustang convertible, five BMW M3s worth $192,560, two Ducatis worth $31,834, a Chrysler sedan, and a $29,216 BMW 323i. It was snazzy machinery, but a well-dressed young man driving an M3 in L.A. was not a sight that aroused suspicion.

Gomez was disposing of the proceeds rather more efficiently. Maybe it was an outgrowth of his skill at crossword puzzles, but he had become a poker player of astonishing talent. His routine was to enter a casino at 8 p.m., armed with $10,000 to $100,000 in cashier's checks that Nichols had drawn on the Lakewood account. He'd convert those checks into poker chips and play all night. His specialty was pai gow poker. He often bet $600 per hand and could play 70 hands nightly. A Bicycle Casino employee recalled, "We once lost $500,000 to Buddha in six months—our biggest loss." A pro player named Barbara Enright said, "I once saw Buddha win close to $1 million in a single session."

In that fashion, Miracle Cars proceeds were bewilderingly mingled with whatever sums Gomez won or lost, all of it held for however long he desired in the form of chips. The chips could be freely converted back to cash at any of the five local casinos. As long as Gomez didn't convert more than $10,000 at any one casino during any one day, no "cash transaction report" would be filed with the IRS. With five casinos handy, he could convert $50,000 daily, $1.5 million monthly. How much of that money found its way back to Gomez's pockets—money the IRS today says is "untraceable and thus untaxable"—is anybody's guess. All that's certain is that by December 2000, Robert Gomez, a.k.a. Buddha, was considered the top gambler in Southern California card parlors.

Back in the Midwest, meanwhile, Miracle Cars affairs had turned less rosy. Buyers were impatient for their cars. Some had been waiting for three years. Gomez's response, in November 2000, was to arrange a morale-boosting junket to Las Vegas for the most valued investors. Recalls one: "We stayed at the Aladdin. Mr. Gomez took us to magic shows, to Hoover Dam, bought all our meals. He bought me a coat and some cologne. He bought outfits for some of the women. He paid cash for everything, had a wad two inches thick."

Investors still weren't satisfied. They now demanded to know the vehicles' whereabouts. As if by magic, receipts began circulating on letterhead belonging to South Bay Toyota and Pay Less Storage. The documents indicated the cars were being conscientiously serviced and stored on secure lots around L.A.

Nichols leapt into the fray himself. In March 2002, he hosted his own investors' meeting in a banquet room at the Smoke House restaurant in Burbank, California. Buyers flew in from all over the country. They were mesmerized by Nichols's confidence, by his charm, by his beautifully tailored suit. But they were furious to learn the cars would remain in probate another 12 months. Everybody complained. Some asked for refunds. A Seattle buyer trotted to the parking lot to photograph Nichols's license plate.

It marked the beginning of the end, of course. And the denouement was surely hastened by the five-foot-tall Higginsville sheriff, who'd already called the district attorney in Kansas City. She reported that a local woman—Corinne Conway—was almost certainly hip deep in a scam so vast that the little Higginsville PD didn't want to touch it. The DA alerted an IRS agent and a federal postal inspector, a duo that had little trouble following the money. Recalls U.S. Treasury agent Gary Marshall: "Over and over, we'd watch car buyers' checks go to Conway in Missouri to Baker in Memphis to Nichols in California to Gomez in the casinos." By tracking bank records, the feds were able to determine that Miracle Car proceeds by then amounted to $21.1 million. From that sum, $8.6 million had been paid back in refunds to impatient customers. That left the four "estate managers"—Nichols, Gomez, Baker, and Conway—with a tidy little profit of $12.5 million. It was an amount, not coincidentally, that also represented what duped buyers had lost.

Of the gravy, $8.7 million got funneled into casinos. It is money, says Marshall, that simply remains "missing in action."

As the feds tapped on calculators, the DA contacted probate courts nationwide, searching for a John Bowers. No such gentleman turned up. Then they beat the bushes for his elusive lawyers. Same result. "If such men ever existed," says Marshall, "they were actors."

And, of course, there were no cars.

At 6 a.m. on June 10, 2002, 27-year-old Robert Gomez was arrested in Larry Flynt's Hustler Casino in Gardena, California. He was playing pai gow poker. In front of him lay $818,000 in chips. James Nichols surrendered to federal agents two weeks later—almost five years after his mother first started taking orders for cars from church members. Found later in Nichols's closet was an unopened FedEx box containing another $269,000 in money orders—proceeds he hadn't even gotten to.

The Midwest "finders"—Conway and Baker—pleaded guilty to fraud and to felony tax evasion. The two men, however, took their chances before a jury in Kansas City, where they faced charges of interstate fraud and money laundering. Assistant U.S. Attorneys Dan Stewart and Curt Bohling had little difficulty flattening the duo with 118 exhibits and 18,000 pages of incriminating receipts, bank statements, and memos. Victims nationwide were only too happy to vent spleen on the witness stand. To mesmerized jurors, the prosecutors explained that the scam's dark beauty was the ease with which it engendered trust: Many of the cars were sold by pastors and church elders. And every time a whale was hooked—a car dealer or sports star—his mere participation proved to five or six others that the deal was sound. Neither did it hurt that Nichols and Gomez had led such demure lifestyles: no drugs, no parties, no penthouses, no trappings of wealth save a BMW or two. And always there was that most persuasive of deal clinchers: the promise of a full refund, the one element of the scam that was, in fact, legit.

On June 6, 2003, U.S. District Judge Nanette Laughrey read the counts and the verdicts. In total, she pronounced Nichols and Gomez guilty 40 times. She went on to seize two vehicles that had belonged to Nichols at the time of his arrest—a white BMW 323i and a yellow Ducati M996.

The irony of that final motion was not lost on prosecutor Stewart. "Year after year, these guys sold thousands of desirable vehicles that did not exist," he said. "Looks like we finally found two that did."

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

10 Best Sedans for Snow Autobytel.comautobytel Car-buying-guides Features

Source: https://www.caranddriver.com/features/a15133983/the-miracle-cars-feature/